Predictors of accessing seasonal malaria chemoprevention medicines through non-door-to-door distribution in Nigeria | Malaria Journal

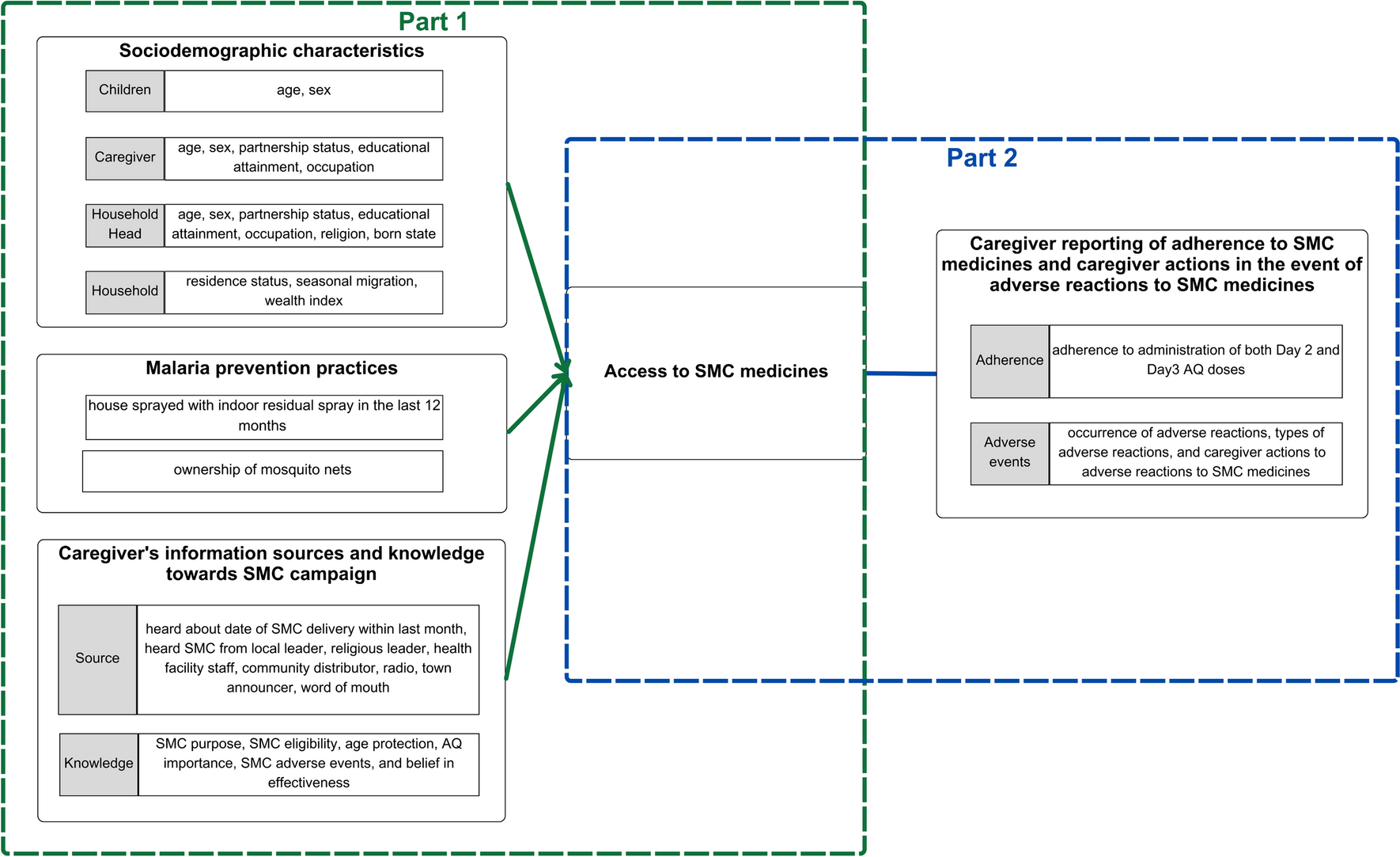

Proportion of children receiving SMC medicines through non-DDD

The final analytic sample included data from 24,003 caregivers of eligible children who received Day 1 SPAQ in the final cycle of SMC between 2021 and 2022 from Nigeria (Fig. 3). The proportion of children receiving SMC medicines but were not visited by CDs (non-DDD access to SMC medicines) was 1.0% (238 of 24,003). In addition, there was 0.3% (76 of 23,765) of children received medicines outside but not at the time of household visit by CDs (non-DDD access to SMC medicines). Therefore, the overall proportion of eligible children who accessed SMC medicines through non-DDD was 1.3% (314 of 24,003). In the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), however, there was 14.2% (232 of 1635) eligible children did not receive SMC medicines, and 2.6% (37 of 1403) of those recipients accessed medicines through non-DDD (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Sociodemographic characteristics of children, caregivers, and heads of household, households receiving SMC medicines through non-DDD

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of children, caregivers, and households accessing SMC medicines through DDD and non-DDD. Caregivers in the non-DDD group were more likely to be female, younger, with higher education level, and non-partnered. Heads of household accessing SMC via non-DDD were more likely to be younger, highly educated, engaged in sales/service/professional work, Muslim, and born outside of the state of current residence. Households in the non-DDD group were more likely to reside in the implementing areas after annual SMC initiation, experience cyclic or periodic migration at least once a year, and have higher wealth. Furthermore, non-DDD was associated with ownership of mosquito nets and indoor residual spray. Caregivers accessing SMC via non-DDD sources were more likely to have heard the date of SMC distribution in the one-month period prior to the final cycle, and to have ever heard about SMC from local leaders, radio, and town announcers. However, caregivers accessing SMC via non-DDD were less likely to have knowledge of the purpose, age eligibility, reason for the eligible age range for SMC, awareness of the importance of AQ and adverse reactions, and belief in the effectiveness of SMC.

Distribution of channels to non-DDD access to SMC medicines

More than one-third (39.5%, 120 of 314) and one-fifth (25.4%, 79 of 314) of channels to non-DDD access to SMC medicines were via health facility staff, and CDs in another location, respectively (Fig 4). Family and friends accounted for 15.5% (52 of 314) of access to SMC medicines through non-DDD. Other channels to obtain SMC medicines included fixed point distribution by CDs (9.7%, 30 of 314), unofficial fixed-point distribution (1.7%, 7 of 314), private purchase (3.6%, 8 of 314), and others (4.6 %, 18 of 314) (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for detailed definitions).

Factors predicting access to SMC medicines

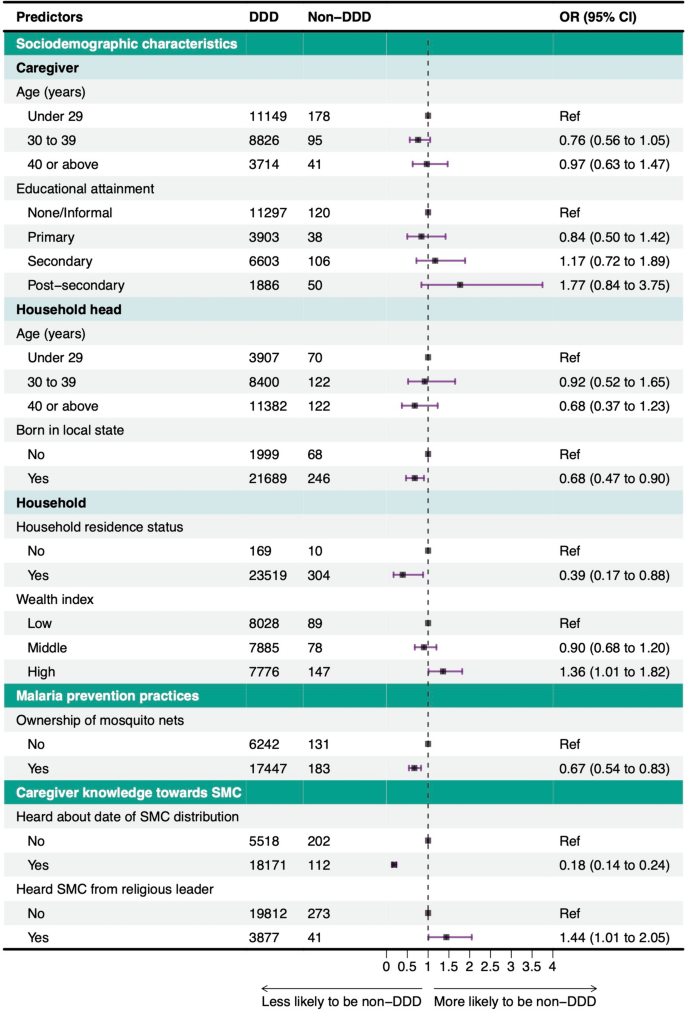

Figure 5 presents the results of the multiple logistic regression model after forward stepwise selection. After mutual covariate adjustment, odds of access to SMC medicines through non-DDD were lower among children in households where heads of household were born in the local state than those with heads of household born outside of the state (OR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.90). Similarly, children in households residing in the same state since the first cycle of the SMC round had lower odds of accessing SMC medicines through non-DDD (OR = 0.39, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.88). Compared with households with low wealth index, those categorized as having high wealth index had higher odds of accessing SMC medicines through non-DDD (OR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.82). Households that owned mosquito nets had lower odds of accessing SMC through non-DDD than households that did not have mosquito nets (OR = 0.67, 95%CI 0.54 to 0.83). Caregivers that heard the date of SMC distribution within the last month (ie, one-month period prior to the final SMC cycle) had lower odds of accessing SMC medicines through non-DDD than caregivers that did not hear the date of SMC delivery date within the last month (OR = 0.18, 95%CI 0.14 to 0.24). Caregivers who ever heard of SMC from a religious leader had higher odds of accessing SMC through non-DDD (OR = 1.44, 95% CI 1.01–2.05). Results of univariate regressions are shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Multivariate logistic regression results of factors associated with access to SMC medicines (N = 24,003). The reference line at 1 indicates no increase or decrease in the likelihood of access to SMC outside household visits. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are also plotted. SMC seasonal malaria chemoprevention, DDD door-to-door distribution, Ref Reference category, OR (adjusted) Odds ratio

Caregiver reporting of adherence to complete administration of SMC medicines and caregiver actions in the event of adverse reactions

Caregivers who accessed SMC medicines through non-DDD were less likely to adhere to administration of both Day 2 and Day 3 AQ doses than those accessing medicines through DDD (86.74% vs. 98.50%; F(1, 24.002) = 237.226, p < 0.001) (Table 2). The proportion of caregivers of eligible children receiving SMC medicines who reported adverse reactions was 16.03% (3,827 of 24,003). There was no significant difference in the occurrence of caregiver-reported adverse reactions between DDD and non-DDD (16.01% vs. 17.89%; F(1, 24.002) = 0.617, p = 0.432). However, caregivers who accessed SMC medicines through non-DDD were more likely to report their child exhibiting yellow eyes than those who obtained SMC medicines through DDD (41.74% vs. 6.99%; F(1, 24.002) = 69.443, p < 0.001) . Loss of appetite was more common among children in household with access via DDD compared with non-DDD (11.73% vs. 1.83%; F(1, 24.002) = 8.237, p = 0.004).

There were differences in caregiver self-reported adverse reactions to SMC medicines among children between DDD and non-DDD groups. Caregivers that accessed SMC medicines through non-DDD were less likely to report adverse reactions to CDs or health facility personnel than caregivers that accessed SMC medicines through DDD (61.63% vs. 78.64%, F(1, 24.002) = 6.983, p = 0.008 ).

Table 2 shows differences in reasons for non-reporting of adverse reactions to SMC medicines in children. In households accessing SMC through non-DDD, the proportion of caregivers who did not report adverse events because they did not know they should report them was approximately twice as high compared with households accessing SMC through DDD (68.68% vs. 37.34%). Conversely, the proportion of caregivers who considered adverse reactions experienced by their children as mild was approximately two times lower among households accessing SMC through non-DDD than those accessing SMC through DDD (17.67% vs. 49.22%).

Results of differences between non-DDD access to SMC medicines in caregiver self-reported adherence to SMC medicines and caregiver actions in the event of adverse reactions to SMC medicines are shown in Additional file 1: Table S4. No statistically significant difference was found in caregivers reporting adherence to AQ administration (88.98% vs. 80.14%; F(1, 24.002) = 3.639, p = 0.057) and caregivers reporting to SMC distributors or health facility personnel in the event of children’s adverse reactions (56.19% vs. 79.12%; F(1, 24.002) = 2.215, p = 0.143) between non-DDD via SMC distributors or health facility personnel, and informal non-DDD.

Ethel Purdy – Medical Blogger & Pharmacist

Bridging the world of wellness and science, Ethel Purdy is a professional voice in healthcare with a passion for sharing knowledge. At 36, she stands at the confluence of medical expertise and the written word, holding a pharmacy degree acquired under the rigorous education systems of Germany and Estonia.

Her pursuit of medicine was fueled by a desire to understand the intricacies of human health and to contribute to the community’s understanding of it. Transitioning seamlessly into the realm of blogging, Ethel has found a platform to demystify complex medical concepts for the everyday reader.

Ethel’s commitment to the world of medicine extends beyond her professional life into a personal commitment to health and wellness. Her hobbies reflect this dedication, often involving research on the latest medical advances, participating in wellness communities, and exploring the vast and varied dimensions of health.

Join Ethel as she distills her pharmaceutical knowledge into accessible wisdom, fostering an environment where science meets lifestyle and everyone is invited to learn. Whether you’re looking for insights into the latest health trends or trustworthy medical advice, Ethel’s blog is your gateway to the nexus of healthcare and daily living.