What we know about the links between microbiota and mental health

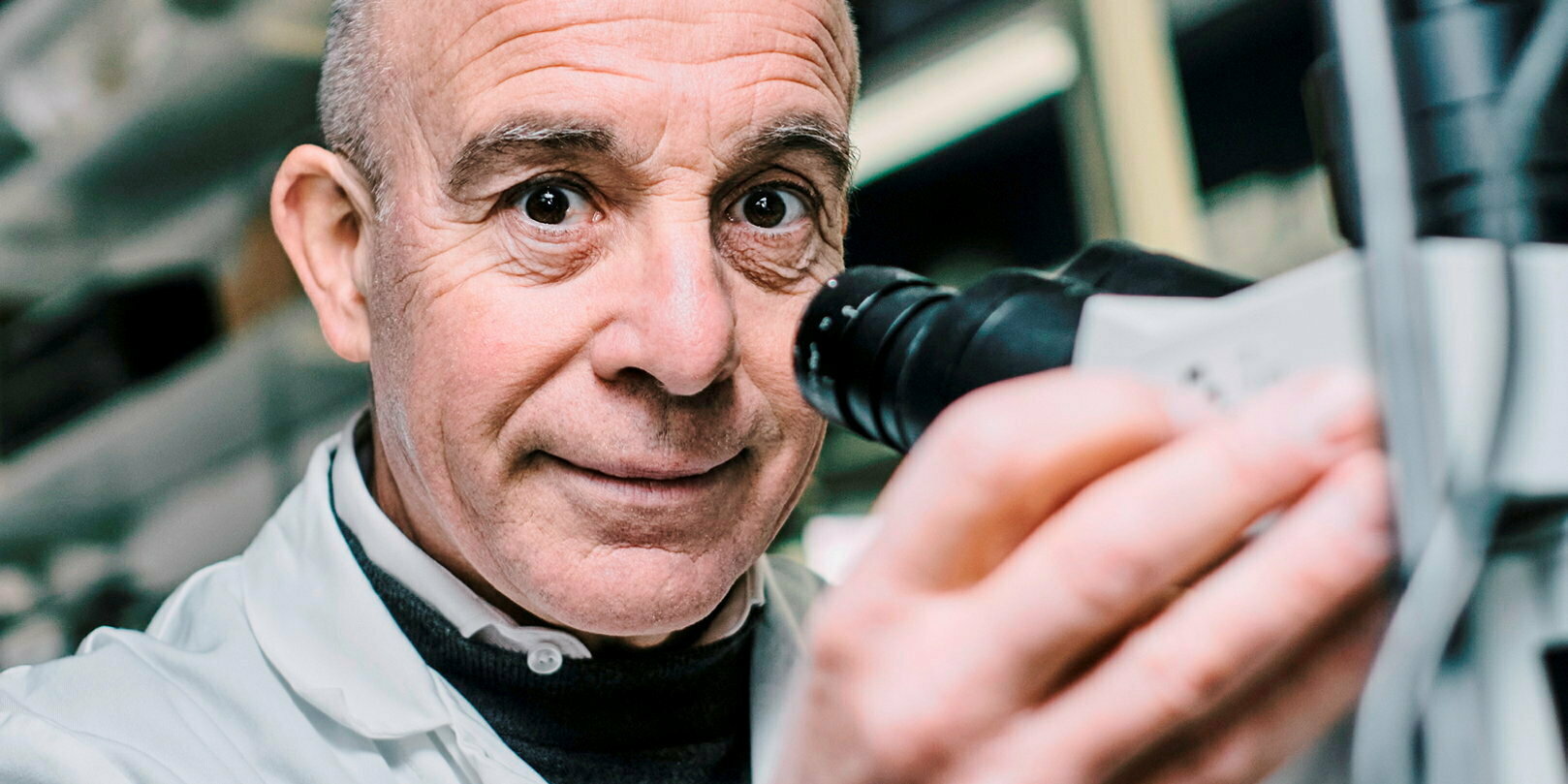

QGone are the days when our brain was considered the undisputed conductor of our body. In shaping our thoughts and regulating our brain functions, the colonies of microorganisms in our intestines have their say. To the point that we must cede part of our free will to them, according to Pierre-Marie Lledo, research director at the CNRS and head of the neuroscience department at the Pasteur Institute, who describes us as “ microbial men “.

Point : In your work, you consider the brain from a global perspective.

Pierre-Marie Lledo: Yes, we no longer limit ourselves to looking under the skull to understand it better. On the contrary, we are part of the movement which consists of studying it by observing its relationships with the rest of the body. Particularly with the intestinal microbiota on which we have been working for five years. The bacteria that colonize our digestive tract constantly “talk” to the brain about various things, using different communication pathways.

How do the stomach and the brain communicate?

First through the bloodstream. The intestine is the most richly vascularized organ in our body, and it is quite logical: from the food passing through it, nutrients intended to be absorbed into the blood are extracted. But pieces of the walls of intestinal bacteria – which “break off” when they divide – are also able to cross the barrier of the intestinal mucosa and enter the general circulation. These bacterial fragments have receptors in the body to which they attach specifically. Until then, they had only been spotted on the surface of immune cells. But my team and I had the great surprise, last year, to discover that, in mice, these receptors were also expressed everywhere in the brain.

Do these bacterial fragments from the microbiota really attach to brain receptors?

To ensure this, we administered radioactive bacteria to the mice in order to trace them. It was found that these tracers passed a first barrier, that of the intestinal mucosa, and were found in the blood. Then a second, made up of the blood-brain barrier (which envelops the brain and isolates it from the rest of the body, Editor’s note). Three or four hours after ingestion, they attached to receptors in the brain. We published this work in 2022 in Science.

What is the role of this chemical “connection” of bacteria in the brain?In our study, we chose to focus on a very specific brain area: that of the hypothalamus. It is a region that controls many of our vital functions: from our food intake to maintaining our body temperature. In our mice, we deactivated the receptors expressed on the surface of hypothalamus neurons. We noticed that our mice couldn’t stop eating and were gaining weight.

This sheds light on one of the roles of bacteria in the microbiota: they send a message of satiety to the central nervous system by exerting feedback on these neurons to slow down their activity. The feeling of fullness is therefore not only due to the tension of the stomach walls, the rise in blood sugar or hormones, as one might have thought. It’s no wonder that bacteria also make themselves heard and ask us to put down our fork. The more we feed them, the more they proliferate. They therefore anticipate a possible overpopulation!

Could this discovery also teach us something about overweight and obesity?

Obesity is a multifactorial disease, potentially linked to psychological disorders, biological or genetic factors. We can also imagine that the eating disorders underlying the disease are linked to mutations on these receptors which would lead to a deficit in the reception of microbial signals. We would like to explore this avenue. This would not be the first time that our microbiota “drives” our brain and our health. The link between microbiota and mental health, for example, is well established.

That is to say, it dictates our moods?

Yes, in part. We already knew that an unbalanced intestinal microbiota – we speak of dysbiosis – was linked to a state of mental stress. But we looked at the biological mechanisms. As in the control of satiety, bacterial substances are involved. No pieces of bacteria this time, but postbiotics. Namely substances produced by bacteria, which should be seen as small chemical factories. We transferred the unbalanced microbiota from an anxiety-depressive animal to a healthy animal. Who also “inherited” these symptoms.

Anxiety and depression are therefore contagious through the microbiota. In our experiment, the blood of the mouse recipient of the “stressed” microbiota became rarefied in certain lipid compounds from the arachidonic acid family, from which endocannabinoids are derived. There was therefore a disappearance of signals that we are all capable of producing thanks to our microbiota and which activate the cannabinoid receptors in the brain. Without these signals, symptoms of anxiety and depression set in. Dysbiosis also caused the disappearance of an essential amino acid: tryptophan. Essential, because tryptophan is the building block that builds serotonin.

Serotonin, which is often called the happiness hormone?

It is a neurotransmitter, and it is precisely the level of serotonin that we try to boost in the brains of depression patients. For this, doctors often rely on a family of drugs called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the best known representative of which is certainly fluoxetine (Prozac). To put it simply, these drugs prevent the loss of serotonin in the synapses, that is to say during its passage between two neurons.

But there still has to be enough at the start! These treatments do not work for everyone, far from it: it is estimated that 30% of patients are resistant to them. Their microbiota could be the explanation for this therapeutic failure. Because only 20% of the tryptophan that passes into the brain to serve as “raw material” for the production of serotonin is taken directly from what we eat. The remaining 80% is produced by the microbiota. So if the main source of the microbiota is dried up, too little serotonin reaches the brain. There is no need to persist in taking SSRIs, or to increase the doses. This is the case in animals and we imagine that it is the same for humans. Better to review the treatment §

Ethel Purdy – Medical Blogger & Pharmacist

Bridging the world of wellness and science, Ethel Purdy is a professional voice in healthcare with a passion for sharing knowledge. At 36, she stands at the confluence of medical expertise and the written word, holding a pharmacy degree acquired under the rigorous education systems of Germany and Estonia.

Her pursuit of medicine was fueled by a desire to understand the intricacies of human health and to contribute to the community’s understanding of it. Transitioning seamlessly into the realm of blogging, Ethel has found a platform to demystify complex medical concepts for the everyday reader.

Ethel’s commitment to the world of medicine extends beyond her professional life into a personal commitment to health and wellness. Her hobbies reflect this dedication, often involving research on the latest medical advances, participating in wellness communities, and exploring the vast and varied dimensions of health.

Join Ethel as she distills her pharmaceutical knowledge into accessible wisdom, fostering an environment where science meets lifestyle and everyone is invited to learn. Whether you’re looking for insights into the latest health trends or trustworthy medical advice, Ethel’s blog is your gateway to the nexus of healthcare and daily living.